Q-switched Lasers

Definition: lasers which emit optical pulses, relying on the method of Q switching

More general term: pulsed lasers

More specific term: actively or passively Q-switched lasers

German: gütegeschaltete Laser

Categories: lasers, light pulses

How to cite the article; suggest additional literature

Author: Dr. Rüdiger Paschotta

A Q-switched laser is a laser to which the technique of active or passive Q switching is applied, so that it emits energetic pulses. Typical applications of such lasers are material processing (e.g. cutting, drilling, laser marking), pumping nonlinear frequency conversion devices, range finding, and remote sensing.

Note that the article on Q switching contains more details on Q-switching techniques; it also contains a video explaining the basic principle of this method of pulse generation.

Q-switched lasers can be pumped either continuously or with pulses, e.g. from flash lamps (particularly for low pulse repetition rates). For continuous pumping, the gain medium should have a long upper-state lifetime to reach a high enough stored energy rather than losing the energy as fluorescence. In any case, the saturation energy should not be too low, because this could lead to excessive gain, so that the premature onset of lasing is more difficult to suppress. The latter problem can occur particularly for fiber lasers. On the other hand, a too high saturation fluence can make efficient energy extraction difficult.

Types of Q-switched Lasers

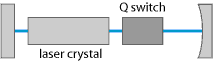

The most common type is the actively Q-switched solid-state bulk laser. Solid-state gain media have a good energy storage capability, and bulk lasers allow for large mode areas (thus for higher pulse energies and peak powers) and shorter laser resonators (e.g. compared with fiber lasers). The laser resonator contains an active Q switch – an optical modulator, which in most cases is an acousto-optic Q switch.

For wavelengths in the 1-μm spectral region, the most common pulsed lasers are based on a neodymium-doped laser crystal such as Nd:YAG, Nd:YVO4, or Nd:YLF, although ytterbium-doped gain media can also be used. A small actively Q-switched solid-state laser may emit 100 mW of average power in 10-ns pulses with a 1-kHz repetition rate and 100 μJ pulse energy. The peak power is then ≈ 9 kW. The highest pulse energies and shortest pulse durations are achieved for low pulse repetition rates (below the inverse upper-state lifetime), at the expense of somewhat reduced average output power. A somewhat larger Nd:YAG laser with a 10-W pump source (e.g. a diode bar) can reach pulse energies of several millijoules. Nd:YVO4 is attractive particularly for short pulse durations and high pulse repetition rates, or for operation with low pump power.

Q-switched lasers with longer emission wavelengths are often based on erbium-doped gain media such as Er:YAG for 1.65 or 2.94 μm, or thulium-doped crystals for ≈ 2 μm.

Significantly larger pulse energies can be obtained from amplifier systems (MOPAs). For high average powers combined with moderate pulse energies, fiber MOPAs, also called MOFAs, can be used.

Particularly for low pulse repetition rates, lamp pumping can be an economically favorable option, since discharge lamps are much cheaper than laser diodes for a given peak power. For higher powers, however, diode pumping becomes more attractive, also because thermal effects in the laser crystal are strongly reduced.

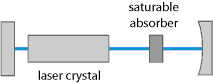

A passively Q-switched laser contains a saturable absorber (passive Q switch) instead of the modulator. For continuous pumping, a regular pulse train is obtained, where the timing of the pulses usually cannot be precisely controlled with external means, and the pulse repetition rate increases with increasing pump power. The most frequently used saturable absorbers for 1-μm lasers are Cr:YAG crystals.

Passively Q-switched microchip lasers have particularly compact setups. Such lasers typically emit pulses with energies between nanojoules and a few microjoules, average output powers of some tens of milliwatts, and repetition rates between a few kilohertz and a few MHz.

Generally, passively Q-switched lasers are more limited in average output power than actively Q-switched versions, since saturable absorbers dissipate some of the energy, so that limiting thermal effects can occur. Note that saturable absorbers usually have some nonsaturable losses, which often increase the dissipated energy well beyond the level which is unavoidable in principle.

Particularly some of the smaller Q-switched lasers, but also some lasers with longer resonators containing an optical filter such as a volume Bragg grating, operate on a single axial resonator mode. This leads to a clean temporal shape and to a small optical bandwidth, often limited by the pulse duration. Other lasers oscillate on multiple resonator modes, which leads to mode beating effects: the output optical power is modulated with frequencies which are integer multiples of the resonator round-trip frequency.

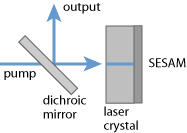

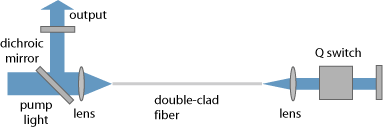

Fiber lasers can also be actively or passively Q-switched. However, all-fiber devices are fairly limited in terms of performance, whereas Q-switched fiber lasers containing bulk-optical elements (e.g. an acousto-optic Q switch, see Figure 4) are less robust and still less powerful than bulk lasers. The relatively small mode areas (even when using large mode area fibers) introduce problems with fiber nonlinearities and laser-induced damage, which set limits on the pulse energies and particularly the peak powers achievable. Note also that the typically very high laser gain in a fiber laser has important effects on the laser dynamics; in particular, it can lead to the formation of a complicated temporal sub-structure.

On the other hand, high-power fiber amplifiers are suitable for amplifying pulse trains with high average power but moderate pulse energy. Some degree of nonlinear pulse distortion in such an amplifier is often acceptable for applications.

Design Issues

Depending on the design goals for a Q-switched laser, different solutions can be appropriate. In the following, some possible goals, encountered issues and trade-offs are listed:

- For short pulse durations, a short laser resonator and high laser gain are required. The shortest pulses are achieved with microchip lasers (see above), because these can have extremely short resonators, but the pulse energies achievable are moderate. Short pulse durations (a few nanoseconds) combined with millijoule pulse energies are possible with compact solid-state lasers, particularly with end-pumped versions due to their higher gain. Thin-disk lasers allow for very high pulse energies, but are not suitable for very short pulses owing to their relatively small gain.

- High pulse energies require good energy storage. For continuous pumping, this means that a long upper-state lifetime is desirable. This results in advantages for ytterbium-doped gain media, e.g. Yb:YAG as compared with Nd:YAG, although these typically have lower gain and therefore generate longer pulses.

- A too high gain should actually be avoided, since it brings with it the risk of losing energy via ASE or parasitic lasing.

- The pulse repetition rate can often be varied in a large range, but this influences not only the pulse energy achievable, but also the pulse duration.

- At high optical intensities, the laser-induced damage of intracavity components such as laser mirrors can be a problem. One therefore requires resonator designs with sufficiently large mode areas not only in the laser crystal but also on all resonator mirrors and in the Q-switch. Particularly in combination with a short resonator length, this can be difficult to achieve. Numerical optimization of resonator designs can sometimes lead to significantly improved performance values, together with improved stability, ease of alignment, and a long lifetime.

- A reduced emission linewidth can be achieved with injection seeding.

Applications of Q-switched Lasers

Q-switched lasers have a wide range of applications. Some examples:

- laser material processing, e.g. laser cutting, laser drilling, laser marking, laser patterning

- laser rangefinders

- LIDAR for 3-dimensional imaging

- laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy

- medical applications, e.g. dermatology and tattoo removal

- pumping devices for nonlinear frequency conversion, e.g. pulsed optical parametric oscillators

- fluorescence spectroscopy

Laser Safety

Note that the high pulse energies and peak powers can raise serious laser safety issues even for lasers with low average output power. A single shot into an eye will in many cases be the last thing that an eye has seen. Such risks can be substantially reduced by using Q-switched lasers operating at eye-safe wavelengths.

Suppliers

The RP Photonics Buyer's Guide contains 87 suppliers for Q-switched lasers. Among them:

Lumibird

Lumibird nanosecond Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers are well known for their ruggeness and versatility. From 5 mJ to 1.5 J at 1064 nm, from single pulse to 400 Hz, they can be diode-pumped (compactness, ease of use) or flashlamp-pumped (high energy), and are available at 532 nm, 355 nm, 266 nm and 1.5 µm. Double pulse models are also proposed for applications in fluid mechanics (PIV).

Teem Photonics

Teem Photonics offers passively Q-switched lasers – Microchip lasers and more powerful devices from the Powerchip laser series. Some are free running, while others are triggerable up to 100 kHz. All can generate sub-nanosecond pulses. Available emission wavelengths are 1535 nm, 1064 nm, 532 nm, 355 nm, 266 nm and 213 nm.

RPMC Lasers

RPMC Lasers offers a wide range of Q-switched laser sources with wavelengths from the UV through the IR. These offerings include DPSS lasers, flashlamp lasers, fiber lasers, and micro lasers/microchip lasers with both active and passive Q-switches.

EKSPLA

Short pulse duration, a wide range of customization options and high stability are distinctive feature of EKSPLA nanosecond Q-switched lasers. Employing latest achievements in laser technologies, our team of dedicated engineers designed wide range of products tailored for specific applications: from compact, simple and robust EKSPLA nanosecond Q-switched DPSS NL230 series lasers for OEM manufacturers to high energy customized flash-lamp multijoule systems for research laboratories.

Second (532 nm), third (355 nm), fourth (266 nm) and fifth (213 nm) (where available) harmonic options combined with various accessories and customization possibilities make these lasers well suited for many OEM and laboratory applications like OPO, OPCPA, Ti:sapphire and dye laser pumping, spectroscopy, remote sensing and plasma research.

Questions and Comments from Users

Here you can submit questions and comments. As far as they get accepted by the author, they will appear above this paragraph together with the author’s answer. The author will decide on acceptance based on certain criteria. Essentially, the issue must be of sufficiently broad interest.

Please do not enter personal data here; we would otherwise delete it soon. (See also our privacy declaration.) If you wish to receive personal feedback or consultancy from the author, please contact him e.g. via e-mail.

By submitting the information, you give your consent to the potential publication of your inputs on our website according to our rules. (If you later retract your consent, we will delete those inputs.) As your inputs are first reviewed by the author, they may be published with some delay.

Bibliography

| [1] | F. J. McClung and R. W. Hellwarth, “Giant optical pulsations from ruby”, J. Appl. Phys. 33 (3), 828 (1962), doi:10.1063/1.1777174 |

| [2] | G. Smith, “The early laser years at Hughes Aircraft Company”, IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 20 (6), 577 (1984), doi:10.1109/JQE.1984.1072445 |

| [3] | J. J. Zayhowski, “Q-switched operation of microchip lasers”, Opt. Lett. 16 (8), 575 (1991), doi:10.1364/OL.16.000575 |

| [4] | L. E. Holder et al., “One joule per Q-switched pulse diode-pumped laser”, IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 28 (4), 986 (1992), doi:10.1109/3.135217 |

| [5] | J. J. Zayhowski and C. Dill III, “Coupled-cavity electro-optically Q-switched Nd:YVO4 microchip lasers”, Opt. Lett. 20 (7), 716 (1995), doi:10.1364/OL.20.000716 |

| [6] | J. J. Degnan, “Optimization of passively Q-switched lasers”, IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 31 (11), 1890 (1995), doi:10.1109/3.469267 |

| [7] | R. S. Conroy et al., “Self-Q-switched Nd:YVO4 microchip lasers”, Opt. Lett. 23 (6), 457 (1998), doi:10.1364/OL.23.000457 |

| [8] | G. J. Spühler et al., “Experimentally confirmed design guidelines for passively Q-switched microchip lasers using semiconductor saturable absorbers”, J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 16 (3), 376 (1999), doi:10.1364/JOSAB.16.000376 |

| [9] | R. Paschotta et al., “Passively Q-switched 0.1 mJ fiber laser system at 1.53 μm”, Opt. Lett. 24 (6), 388 (1999), doi:10.1364/OL.24.000388 |

| [10] | J. A. Alvarez-Chavez et al., “High-energy, high-power ytterbium-doped Q-switched fiber laser”, Opt. Lett. 25 (1), 37 (2000), doi:10.1364/OL.25.000037 |

| [11] | K. Du et al., “Electro-optically Q-switched Nd:YVO4 slab laser with a high repetition rate and a short pulse width”, Opt. Lett. 28 (2), 87 (2003), doi:10.1364/OL.28.000087 |

| [12] | A. A. Fotiadi et al., “Dynamics of a self-Q-switched fiber laser with a Rayleigh-stimulated Brillouin scattering ring mirror”, Opt. Lett. 29 (10), 1078 (2004), doi:10.1364/OL.29.001078 |

| [13] | Y. Wang and C. Xu, “Modeling and optimization of Q-switched double-clad fiber lasers”, Appl. Opt. 45 (9), 2058 (2006), doi:10.1364/AO.45.002058 |

| [14] | L. McDonagh et al., “47 W, 6 ns constant pulse duration, high-repetition-rate cavity-dumped Q-switched TEM00 Nd:YVO4 oscillator”, Opt. Lett. 31 (22), 3303 (2006), doi:10.1364/OL.31.003303 |

| [15] | T. Hakulinen and O. G. Okhotnikov, “8 ns fiber laser Q switched by the resonant saturable absorber mirror”, Opt. Lett. 32 (18), 2677 (2007), doi:10.1364/OL.32.002677 |

| [16] | N. Vorobiev et al., “Single-frequency-mode Q-switched Nd:YAG and Er:glass lasers controlled by volume Bragg gratings”, Opt. Express 16 (12), 9199 (2008), doi:10.1364/OE.16.009199 |

| [17] | R. Horiuchi et al., “1.4-MHz repetition rate electro-optic Q-switched Nd:YVO4 laser”, Opt. Express 16 (21), 16729 (2008), doi:10.1364/OE.16.016729 |

| [18] | A. Steinmetz et al., “Reduction of timing jitter in passively Q-switched microchip lasers using self-injection seeding”, Opt. Lett. 35 (17), 2885 (2010), doi:10.1364/OL.35.002885 |

| [19] | R. Bhandari and T. Taira, “Megawatt level UV output from [110] Cr4+:YAG passively Q-switched microchip laser”, Opt. Express 19 (23), 22510 (2011), doi:10.1364/OE.19.022510 |

| [20] | R. W. Hellwarth, “Control of fluorescent pulsations”, in Advances in Quantum Electronics (ed. R. Singer), Columbia University Press, New York (1961), p. 334 |

| [21] | R. Paschotta, "Noise in Laser Technology – Part 2: Fluctuations in Pulsed Lasers" |

| [22] | R. Paschotta, case study on an actively Q-switched Nd:YAG laser |

See also: Q switching, Q switches, lasers, nanosecond lasers, lamp-pumped lasers, laser safety, laser-induced damage, The Photonics Spotlight 2006-09-16, The Photonics Spotlight 2009-03-07

and other articles in the categories lasers, light pulses

This encyclopedia is authored by Dr. Rüdiger Paschotta, the founder and executive of RP Photonics Consulting GmbH. How about a tailored training course from this distinguished expert at your location? Contact RP Photonics to find out how his technical consulting services (e.g. product designs, problem solving, independent evaluations, training) and software could become very valuable for your business!

|

If you like this page, please share the link with your friends and colleagues, e.g. via social media:

These sharing buttons are implemented in a privacy-friendly way!