Fiber Simulation Software

Definition: software for numerical simulations on fiber devices

German: Faser-Simulationssoftware

Categories: fiber optics and waveguides, optical amplifiers, methods, physical foundations

How to cite the article; suggest additional literature

Author: Dr. Rüdiger Paschotta

Many aspects of the operation of passive and active fiber-optic devices are relatively complex. Therefore, numerical tools are required for analyzing various physical details. The resulting understanding can be used for the optimization both of the design of fiber components and of their use. In the following, an overview on different aspects is given which are often relevant for the development of active and passive fiber devices.

Calculation of Fiber Modes

Of the many modes of fibers, the guided modes are of particular interest, as they are important e.g. for coupling light into a fiber and for the beam quality of the output. The mode properties are determined by the refractive index profile of the fiber. Properties of interest can be, for example,

- the shapes of the amplitude or intensity distribution of modes

- mode radii and effective mode areas

- the overlap with the doped core in a rare-earth-doped fiber

- effective refractive indices

- chromatic dispersion, e.g. the group velocity dispersion versus wavelength (calculated by differentiation of the frequency-dependent phase delay)

- bend losses versus bend radius

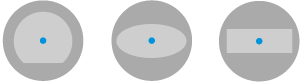

Most all-glass fibers have a radially symmetric refractive index profile and also exhibit only weak index contrasts, so that approximations for weakly guiding waveguides can be used. Under these circumstances, the LP modes of the fiber can be calculated with a mode solver based on relatively simple numerical methods. This also means that the calculation can be rather fast – the complete guided mode properties can be calculated within a second on an ordinary PC, even if there are many such modes.

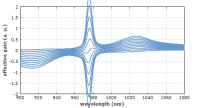

Figure 1 shows an example for a few-mode fiber, where the wavelength is varied. While for the shortest wavelength (750 nm) the fiber has modes with 6 different intensity profiles, more and more modes disappear for longer wavelengths, until the fiber is single-mode.

Mode solvers based on substantially more sophisticated algorithms are required for other cases, such as polarization-maintaining fibers lacking radial symmetry, and in particular for photonic crystal fibers. The latter also exhibit very strong index contrasts, i.e., the weakly guiding approximation can not be applied. There are various numerical techniques, and generally the computation time is much longer than for the simple methods as normally used for all-glass fibers.

Numerical Beam Propagation

Not in all situations, the calculation of fiber modes is both feasible and helpful. For example, the mode calculation is very difficult and rather time-consuming for the pump claddings of some double-clad fibers with irregular profile. It also gives more detailed information than required (hundreds or thousands of detailed mode intensity profiles), while still not fully taking into account the effects of irregular fiber bends. Another example is the behavior of fused fiber couplers, where the modes strongly depend on the local conditions. In such cases, it is often more suitable to numerical simulate the beam propagation.

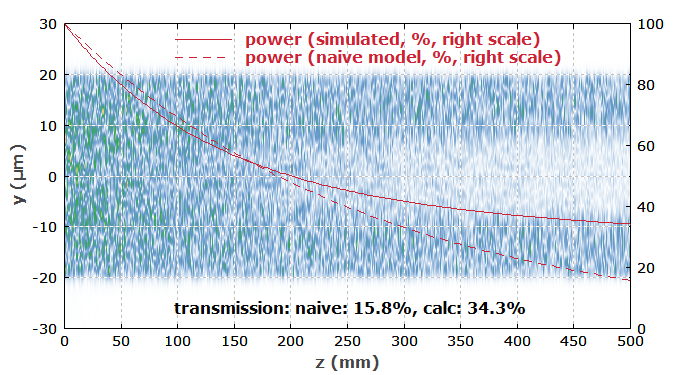

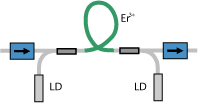

As a first example, Figure 2 shows how pump light gets absorbed in a double-clad fiber with a simple geometry: a circular core in the middle of a circular pump cladding. Here, pump absorption is quite incomplete as some modes have very poor overlap with the doped core. Such a beam propagation model can be easily applied to other geometries, e.g. with an off-centered core, a D-shaped or octagonal core, or with strong bending, which may even be variable along the fiber length.

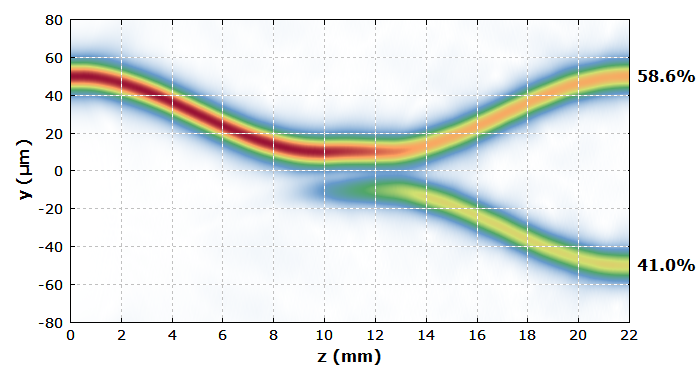

Another example is a fused fiber coupler, where two cores come close together over some distance. Their evanescent fields then touch each other, so that light can couple over. The detailed behavior depends strongly on the gap size, the coupling distance, and the wavelength. Figure 3 shows a typical simulation.

Optical Amplification in Fibers

Optical amplification occurs in fiber lasers and amplifiers, which are usually based on rare-earth-doped fibers. The dopant is usually restricted to the fiber core, but there are also modified designs for special applications e.g. with ring doping around the core.

Behavior of the Laser-active Ions

The interaction of the laser-active ions with the light field can usually be described with rate equation modeling. Differential equations describe the temporal evolution of the excitations of different levels for given optical intensities, and can also be used for calculating steady-state level populations. In many cases (e.g., ytterbium-doped lasers and amplifiers), a simplified gain model, considering only a single metastable state and the ground state, is sufficient for an accurate description. In other cases, however, a more sophisticated gain model needs to be set up, which may take into account multiple metastable levels and various processes which can shuffle ions between the different levels. For example, there can be excited-state absorption, quenching by upconversion processes or energy transfers, possibly even between different types of ions (e.g. in Er/Yb-doped fibers). Ideally, a software allows the user to define arbitrary level schemes and all the relevant processes.

Various spectroscopic data are required for such modeling: effective transition cross sections (for ground-state absorption, excited-state absorption, emission), upper-state lifetimes, quenching or upconversion parameters, etc. On the other hand, a computer model can be an essential tool for extracting such data from results of measurements.

Laser or Amplifier Gain

The resulting laser gain depends on the excitation density of the laser-active ions, but also on the overlap of the fiber modes with the dopant. Therefore, the gain does not only depend on the wavelength, but can also be different for different modes. Fiber designs can be optimized such that higher-order modes experience a lower gain than the favored fundamental mode.

Note that the gain may be saturated not only by an amplified signal, but also by amplified spontaneous emission (ASE). Therefore, ASE has to be calculated as well, at least if the gain is relatively high. (In models for fiber lasers, it can often be neglected.)

Self-consistency in Fiber Lasers and Amplifiers

For calculating the steady state of a fiber laser, but also of a fiber amplifier with counterpropagating pump and signal, one needs to find a self-consistent solution for both the excitation densities and the optical powers. These quantities depend on each other, and neither one is originally known. While relatively simple methods such as the shooting method can be used in simple cases, the task becomes numerically quite demanding in more complicated cases, e.g. when there is also strong amplified spontaneous emission (ASE). Non-optimized algorithms can have serious problems with convergence and computation time when applied to difficult cases.

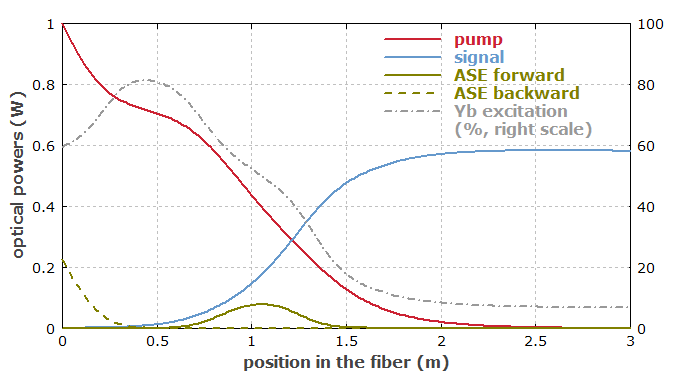

As an example, Figure 4 shows the optical powers and the excitation density in an ytterbium-doped fiber amplifier. Although this example is relatively simple, the behavior of the device would be hard to predict without numerical simulations, as substantial saturation effects from ASE arise, and the distribution of ASE powers depends in complicated ways on the ytterbium excitation profile.

Dynamic Simulations

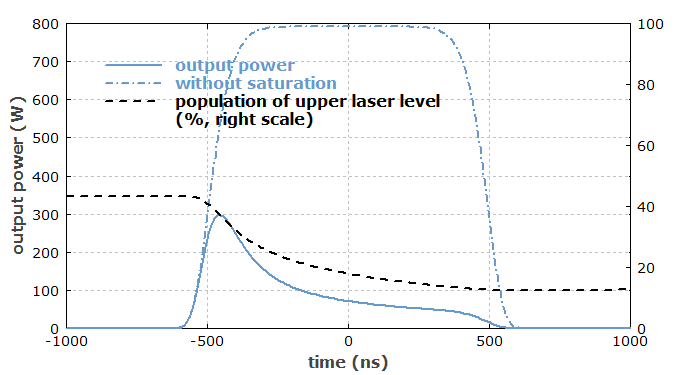

In various cases, not the steady state is of interest, but rather the temporal evolution for time-dependent power inputs. As an example, one may consider a fiber amplifier which is first pumped for some time, so that some energy is stored in the fiber, and then serves to amplify an injected nanosecond pulse. During the pumping phase, the gain raises while the pump absorption decreases; the transmitted residual pump power may increase with time. When the signal pulse is injected, it will saturate the gain, so that the temporal shape of the output pulse can become quite distorted.

Figure 5 shows an example, where a signal input pulse with super-Gaussian temporal shape extracts much of the energy stored in an ytterbium-doped amplifier. The dot-dashed curve shows how the output would evolve without gain saturation. Due to gain saturation, however, the gain drops during the amplification, and the output power gets lower.

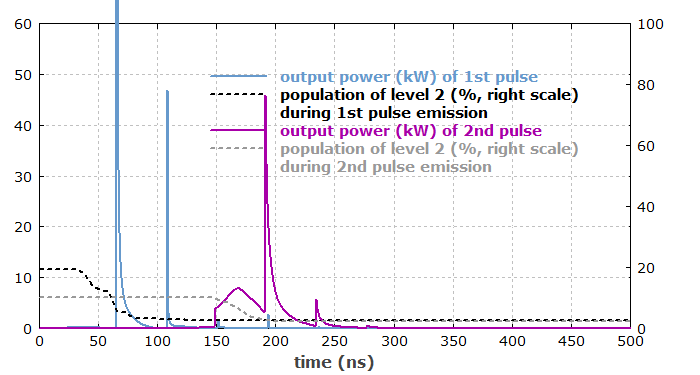

Another example is a Q-switched fiber laser. Here, it is essential to take into account propagation times (which can often be neglected in amplifier models). Lasing begins with ASE, which can be spatially quite variable due to the high gain which fiber devices typically have. As a result, the generated output can exhibit complicated peak structures, which are not observed for Q-switched bulk lasers. Figure 6 shows an example case, where a very fast Q-switch has been assumed. For slower switching, one can obtain quite different pulse shapes.

Note that rather different time scales can be involved in a simulation. Pumping can usually be simulated with rather course numerical time steps, whereas the generation of a Q-switched pulse requires much finer steps. A software which can work only with a fixed step size would then be extremely time-consuming.

Ultrashort Pulse Propagation

Ultrashort pulses can be amplified in a fiber amplifier or generated in a mode-locked fiber laser. Also, one may want to investigate pulse propagation in passive fibers, as used e.g. for delivery to an application. For pulse propagation in the fiber, additional effects need to be taken into account – in particular, the chromatic dispersion and the fiber's nonlinearities (possibly including stimulated Raman scattering). In addition, it may be necessary to treat multiple fibers with different properties in a model and also effects of additional components, such as a saturable absorber for mode locking, an optical filter or an output coupler. (With such features, a fiber simulation software also becomes usable for many bulk-optical devices.)

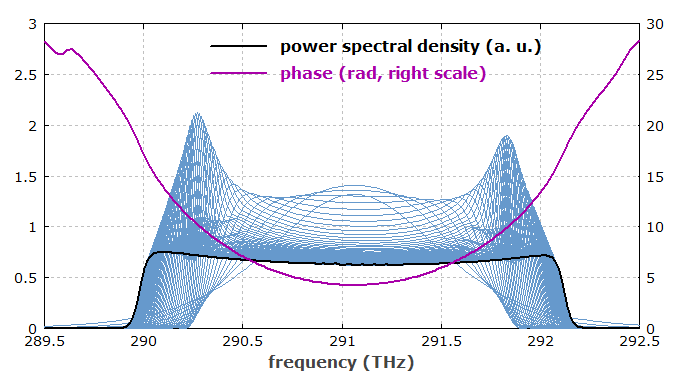

As an example, Figure 7 shows how the optical spectrum of the output pulse of a similariton-type mode-locked fiber laser converges to a nearly rectangular shape within 100 resonator round-trips. One also obtains the spectral phase, which is close to parabolic in the relevant region, so that dispersive pulse compression is not difficult to do.

Generally, ultrashort pulse propagation is substantially more time-consuming to simulate, compared with simple propagation of powers for continuous-wave cases. For finding the steady state e.g. for the amplification of high-repetition rate pulse trains, it is therefore much more efficient to first do a steady-state calculation and then refine the solution as required with ultrashort pulse propagation.

As the resulting processes can be rather complex, it is very desirable to have flexible tools both for arranging different model situations and for inspecting the results. For example, it is useful to inspect the pulses at any location and after any number of round trips in the time and frequency domain, and to store pulses at specified locations for later analysis.

Suppliers

The RP Photonics Buyer's Guide contains 11 suppliers for fiber simulation software. Among them:

RP Photonics

RP Fiber Power simulation software for designing fiber devices: fiber amplifiers, fiber lasers, ASE sources, fiber-optic data links, and passive devices such as multi-core fibers, tapered fibers and fiber couplers. For simpler purposes, there is the free fiber optics software RP Fiber Calculator.

Questions and Comments from Users

Here you can submit questions and comments. As far as they get accepted by the author, they will appear above this paragraph together with the author’s answer. The author will decide on acceptance based on certain criteria. Essentially, the issue must be of sufficiently broad interest.

Please do not enter personal data here; we would otherwise delete it soon. (See also our privacy declaration.) If you wish to receive personal feedback or consultancy from the author, please contact him e.g. via e-mail.

By submitting the information, you give your consent to the potential publication of your inputs on our website according to our rules. (If you later retract your consent, we will delete those inputs.) As your inputs are first reviewed by the author, they may be published with some delay.

See also: fibers, modes, fiber optics, fiber lasers, fiber amplifiers, erbium-doped fiber amplifiers, gain, ultrashort pulses, laser modeling

and other articles in the categories fiber optics and waveguides, optical amplifiers, methods, physical foundations

|

If you like this page, please share the link with your friends and colleagues, e.g. via social media:

These sharing buttons are implemented in a privacy-friendly way!