Passive Mode Locking

Definition: a technique of mode locking, based on a saturable absorber inside the laser resonator

More general term: mode locking

Opposite term: active mode locking

German: passives Modenkoppeln

Categories: lasers, light pulses, methods

How to cite the article; suggest additional literature

Author: Dr. Rüdiger Paschotta

The general aspects of the generation of ultrashort pulses by mode locking are discussed in the article on mode locking. This article focuses on passive mode locking, which can be achieved by incorporating a saturable absorber with suitable properties into the laser resonator (Figure 1).

Most mode-locked lasers are passively rather than actively mode-locked – particularly those used for generating very short femtosecond pulses. However, active mode locking is preferred for some applications where particularly short pulses are not required, but the synchronization with an external electronic signal.

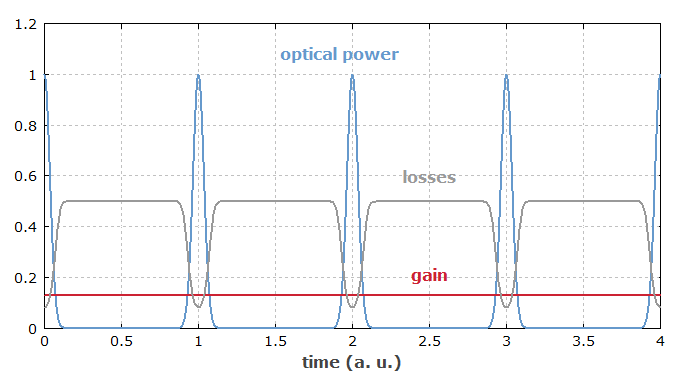

In the following, the steady state of a passively mode-locked laser is considered, where a short pulse is already circulating in the laser resonator. For simplicity, it is assumed that there is a single circulating pulse (i.e. fundamental rather than harmonic mode locking), and a fast absorber (see below for details). Each time the pulse hits the saturable absorber, it saturates the absorption, thus temporarily reducing the losses (Figure 2). In the steady state, the laser gain can be saturated to a level which is just sufficient for compensating the losses for the circulating pulse, whereas any light of lower intensity which hits the absorber at other times will experience losses which are higher than the gain, since the absorber cannot be saturated by this light. The absorber can thus suppress any additional (weaker) pulses in addition to any continuous background light. Also, it constantly attenuates particularly the leading wing of the circulating pulse; the trailing wing may also be attenuated if the absorber can recover sufficiently quickly (see below). The absorber thus tends to decrease the pulse duration; in the steady state, this effect will balance other effects (e.g. chromatic dispersion) which tend to lengthen the pulse.

Compared with active mode locking, the technique of passive mode locking allows the generation of much shorter pulses, essentially because a saturable absorber, driven by already very short pulses, can modulate the resonator losses much faster than any electronic modulator: the shorter the circulating pulse becomes, the faster is the loss modulation obtained. This holds at least for the leading wing of the pulse, where the absorber is bleached, whereas absorber recovery may take some longer time.

In many (but not all) cases, the saturable absorber can also start the mode-locking process. If the pulse generation process begins automatically after switching on the laser, this is called self-starting mode locking. Usually, the laser first starts operation in a more or less continuous way, but with significant fluctuations of the laser power (→ laser noise). In each resonator round trip, the saturable absorber will then favor the light which has somewhat higher intensities, because this light can saturate the absorption slightly more than light with lower intensities. After many round trips, a single pulse will remain (principle of “the winner takes all”). However, self-starting is not always achieved. Generally, slow absorbers are more suitable for self-starting mode locking than fast absorbers. For example, Kerr lens mode-locked lasers are often not self-starting; they run in continuous-wave mode after turning on, and start mode locking only when the user knocks against a resonator mirror. Self-starting may be inhibited e.g. by parasitic reflections in the resonator, by mode pulling effects (which can be related to, e.g., spatial hole burning in the gain medium), or by chromatic dispersion.

Fast and Slow Saturable Absorbers

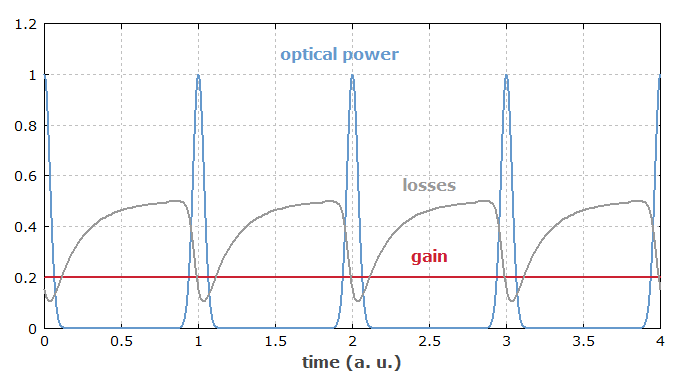

If the absorber recovery time is well below the pulse duration, the absorber is called a fast absorber. In that case, the loss modulation basically follows the variation of the optical power. However, mode locking can also be achieved with a slow absorber, having a recovery time above the pulse duration (see Figure 3).

It turns out that e.g. in a solid-state laser mode-locked with a slow absorber, there is a temporal range with net gain just after the pulses, where the absorber is still in the saturated state. One would normally expect that such a situation can not be stable, because any noise behind the pulse should exhibit exponential growth of its energy, sooner or later destabilizing the pulse. However, both experimental observations and numerical simulations indicate stability even in situations where the absorber recovery time is more than an order of magnitude longer than the pulse duration. An explanation for that mystery was first found in the case of soliton mode locking [13], but unexpected stability had been observed also in simple cases without dispersive and nonlinear effects; that could also be demonstrated with numerical simulations. Finally, in 2001 a subtle mechanism was found to be responsible for the stability [16]: the stronger absorption for the leading edge of the pulse constantly delays the pulse (i.e. shifts the position of the maximum), but not the noise background, so that the latter has a limited time for exponential growth. Based on that analysis, a limit for the allowable absorber recovery time could be derived.

Types of Saturable Absorbers

The crucial intracavity component for passive mode locking is a saturable absorber. The most important type of absorber for passive mode locking is the semiconductor saturable absorber mirror, called SESAM. This is a compact semiconductor device, the parameters of which can be adjusted in very wide ranges, so that appropriately designed SESAMs can be used to mode-lock very different kinds of lasers, in particular solid-state lasers, including different kinds of semiconductor lasers. (See also the article on mode-locked lasers.)

Other saturable absorbers for mode locking are based on quantum dots, e.g. of lead sulfide (PbS) suspended in glasses. Doped-insulator saturable absorbers, as often used for passive Q switching (e.g. Cr:YAG), usually have a too slow recovery for mode locking.

There are also various kinds of artificial saturable absorbers, based on, e.g., nonlinear phase shifts (→ Kerr lens mode locking, additive-pulse mode locking, nonlinear polarization rotation) or on intensity-dependent frequency conversion (nonlinear mirror mode locking [9]).

Dispersion and Nonlinearities

In the picosecond regime of pulse durations, chromatic dispersion usually has only a weak effect. Nonlinearities, in particular the Kerr effect, can be significant, depending on parameters such as the length and material of the laser crystal, the mode area at that place, and the pulse energy and duration.

For femtosecond pulse generation, it is usually required to arrange for dispersion compensation, for example with a prism pair, as shown in the article on mode-locked lasers, or with dispersive mirrors. In many cases, a laser is operated in the anomalous dispersion regime, where the circulating pulse can be a quasi-soliton; this is called soliton mode locking. In the few-cycle pulse duration regime, with ultrabroad pulse spectra, precise compensation of higher-order dispersion is required.

The effects of nonlinearities, in particular of the Kerr nonlinearity, can also be very important in femtosecond lasers. Excessive nonlinear phase shifts can destabilize the pulses or limit the achievable pulse durations. On the other hand, they can play a useful role in soliton mode locking. In fiber lasers, the fiber nonlinearity is often stronger than desirable and thus often limits the achievable pulse durations and/or pulse energies.

Mechanisms of Pulse Formation and Shaping

In the steady state of a mode-locked laser, the pulse parameters are essentially constant, or at least are reproduced after each resonator round trips. This means that there must be a balance of all effects acting on the pulse. The details of this balance, i.e., the importance of various effects and even the whole principle of pulse formation, can depend strongly on the type of laser and the pulse duration regime, not only on the type of saturable absorber. Some examples are discussed in the following:

- Gain saturation during the pulse can be significant in dye lasers and semiconductor lasers, but not at all in doped-insulator solid-state lasers. In the former cases, significant chirp of the pulses can be a consequence. Also, stabilization of the pulse energy by gain saturation is strong in dye lasers and semiconductor lasers, but very weak in solid-state lasers.

- The Kerr effect and the effect of chromatic dispersion can be negligible in picosecond lasers, particularly for those with multi-gigahertz repetition rates, but very strong in femtosecond lasers, particularly in fiber lasers. Both can play a very useful role in soliton mode-locked lasers, whereas much smaller nonlinear phase shifts can have a destabilizing effect in lasers without intracavity dispersion.

- In some mode-locked lasers, the pulse duration obtained depends strongly on the parameters of the saturable absorber. For others (e.g. soliton mode-locked lasers), this influence can be weak, because the absorber plays only a stabilizing role, but is not dominant for pulse shaping.

A comprehensive understanding of the pulse formation and shaping processes is essential for good laser design, with which the best possible performance is achieved. For the detailed study of pulse shaping in mode-locked lasers, numerical pulse propagation modeling can be very useful.

Achievable Pulse Duration

Depending on the particular type of mode-locked laser, the shortest achievable pulse duration can be determined by a number of factors:

- In simple SESAM mode-locked lasers particularly in the picosecond regime, the pulse duration often results from a steady state between gain narrowing and the pulse-shortening effect of the SESAM absorber, which itself depends on details such as modulation depth and degree of saturation. The pulse duration is then inversely proportional to the square root of the ratio of round-trip gain and modulation depth [16], also inversely proportional to the gain bandwidth.

- In the femtosecond regime, the situation is usually further complicated by the influence of chromatic dispersion and nonlinearities. A common technique is (quasi-)soliton mode locking, where the pulse duration is largely determined by the balance of dispersion and Kerr nonlinearity, without a significant direct influence of the gain bandwidth. The pulse duration can then be reduced by reducing the amount of anomalous intracavity dispersion, provided that the circulating pulse stays stable. The stability limit and thus the achievable pulse duration depends on the gain bandwidth, but also on the total intracavity losses, the strength of nonlinearities and other factors.

- In mode-locked fiber lasers, often utilizing more complicated pulse formation mechanisms, the achievable pulse duration may also be strongly influenced by nonlinearities and by higher-order chromatic dispersion.

The shortest pulses generated directly with a passively mode-locked laser have durations around 5.5 fs (see the article on ultrafast lasers). External pulse compression allows for significant further reductions.

Instabilities

The use of a saturable absorber in a laser may not only lead to passive mode locking, but also to passive Q switching, to Q-switched mode locking, or to some noisy mode of operation, if the absorber properties are not appropriate.

Under certain circumstances, Q-switching instabilities can occur, because the saturable absorber usually “rewards” any increase in the intracavity pulse energy above its steady-state value with reduced losses, so that the net gain becomes positive and the pulse energy can rise further. The situation becomes unstable if gain saturation is not strong enough to counteract the destabilizing effect of the absorber. Q-switching instabilities (or Q-switched mode locking) can usually be suppressed by observing certain design guidelines, but in certain parameter ranges – for high pulse repetition rates, in particularly in combination with short pulses or high output powers – this can be challenging.

There is also a range of other types of instabilities, which can be related e.g. to excessive nonlinearities, to an inappropriate degree of absorber saturation, to too slow absorber recovery, to higher-order dispersion, to parasitic reflections, or to inhomogeneous gain saturation. It is not always obvious which of these instabilities is at work, but the required measures usually depend strongly on that.

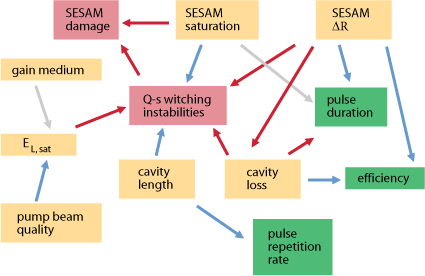

Optimum Design

Optimum design of a mode-locked laser, particularly for operation in extreme parameter regions, must be based on a thorough understanding of the relations between various parameters and effects occurring in such lasers. Figure 4 shows such relations for passively mode-locked lasers in a very simplified form. For example, a high modulation depth ΔR of the saturable absorber (SESAM) normally leads to shorter pulses, but also to an increased tendency for Q-switching instabilities or Q-switched mode locking, and to a reduced power efficiency. Q-switching instabilities are related in various ways to SESAM damage, and can be suppressed in various ways. A thorough understanding of all these relations often allows one to “shift” the problems to a location where they are much more easily solved. For example, SESAM damage issues, which originally sometimes occurred even for fairly moderate output powers, have been solved essentially not by developing SESAMs with higher damage thresholds, but rather by optimizing the overall laser design. This allowed the generation of very high output powers [19] without putting the SESAM under excessive stress.

Questions and Comments from Users

Here you can submit questions and comments. As far as they get accepted by the author, they will appear above this paragraph together with the author’s answer. The author will decide on acceptance based on certain criteria. Essentially, the issue must be of sufficiently broad interest.

Please do not enter personal data here; we would otherwise delete it soon. (See also our privacy declaration.) If you wish to receive personal feedback or consultancy from the author, please contact him e.g. via e-mail.

By submitting the information, you give your consent to the potential publication of your inputs on our website according to our rules. (If you later retract your consent, we will delete those inputs.) As your inputs are first reviewed by the author, they may be published with some delay.

Bibliography

| [1] | H. W. Mocker and R. J. Collins, “Mode competition and self-locking effects in a Q-switched ruby laser”, Appl. Phys. Lett. 7, 270 (1965), doi:10.1063/1.1754253 (first demonstration of passive mode locking, obtained together with Q switching → Q-switched mode locking) |

| [2] | A. J. DeMaria, D. A. Stetser, and H. Heynau, “Self mode-locking of lasers with saturable absorbers”, Appl. Phys. Lett. 8, 174 (1966), doi:10.1063/1.1754541 |

| [3] | E. P. Ippen, C. V. Shank, and A. Dienes, “Passive mode locking of the cw dye laser”, Appl. Phys. Lett. 21, 348 (1972), doi:10.1063/1.1654406 (first continuous-wave mode locking with a saturable absorber) |

| [4] | H. A. Haus, “Theory of mode locking with a fast saturable absorber”, J. Appl. Phys. 46 (7), 3049 (1975), doi:10.1063/1.321997 |

| [5] | H. Haus, “Parameter ranges for CW passive mode locking”, IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 12 (3), 169 (1976), doi:10.1109/JQE.1976.1069112 |

| [6] | K. Sala et al., “Passive modelocking of lasers with the optical Kerr effect modulator”, IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 13 (11), 915 (1977), doi:10.1109/JQE.1977.1069251 |

| [7] | E. P. Ippen et al., “Picosecond pulse generation by passive modelocking of diode lasers”, Appl. Phys. Lett. 37, 267 (1980), doi:10.1063/1.91902 |

| [8] | O. E. Martínez and R. L. Fork, “Theory of passively mode-locked lasers including self-phase modulation and group-velocity dispersion”, Opt. Lett. 9 (5), 156 (1984), doi:10.1364/OL.9.000156 |

| [9] | K. A. Stankov, “A mirror with an intensity-dependent reflection coefficient”, Appl. Phys. B 45, 191 (1988), doi:10.1007/BF00695290 |

| [10] | H. A. Haus et al., “Structures of additive pulse mode locking”, J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 8 (10), 2068 (1991), doi:10.1364/JOSAB.8.002068 |

| [11] | F. Krausz and T. Brabec, “Passive mode locking in standing-wave laser resonators”, Opt. Lett. 18 (11), 888 (1993), doi:10.1364/OL.18.000888 |

| [12] | E. P. Ippen, “Principles of passive mode locking”, Appl. Phys. B 58, 159 (1994), doi:10.1007/BF01081309 |

| [13] | F. X. Kärtner et al., “Stabilization of solitonlike pulses with a slow saturable absorber”, Opt. Lett. 20 (1), 16 (1995), doi:10.1364/OL.20.000016 |

| [14] | S. Tsuda et al., “Mode-locking ultrafast solid-state lasers with saturable Bragg reflectors”, J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2 (3), 454 (1996), doi:10.1109/2944.571744 |

| [15] | C. Hönninger et al., “Q-switching stability limits of cw passive mode locking”, J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 16 (1), 46 (1999), doi:10.1364/JOSAB.16.000046 |

| [16] | R. Paschotta et al., “Passive mode locking with slow saturable absorbers”, Appl. Phys. B 73 (7), 653 (2001), doi:10.1007/s003400100726 |

| [17] | R. Paschotta et al., “Passive mode locking of thin-disk lasers: effects of spatial hole burning”, Appl. Phys. B 72 (3), 267 (2001), doi:10.1007/s003400100486 |

| [18] | R. Paschotta et al., “Soliton-like pulse shaping mechanism in passively mode-locked surface-emitting semiconductor lasers”, Appl. Phys. B 75, 445 (2002), doi:10.1007/s00340-002-1014-5 |

| [19] | E. Innerhofer et al., “60 W average power in 810-fs pulses from a thin-disk Yb:YAG laser”, Opt. Lett. 28 (5), 367 (2003), doi:10.1364/OL.28.000367 |

| [20] | A. Fernandez et al., “Chirped-pulse oscillators: a route to high-power femtosecond pulses without external amplification”, Opt. Lett. 29 (12), 1366 (2004), doi:10.1364/OL.29.001366 |

| [21] | G. Palmer et al., “Passively mode-locked and cavity-dumped Yb:KY(WO4)2 oscillator with positive dispersion”, Opt. Express 15 (24), 16017 (2007), doi:10.1364/OE.15.016017 |

| [22] | F. Saltarelli et al., “Modelocking of a thin-disk laser with the frequency-doubling nonlinear-mirror technique”, Opt. Express 25 (19), 23254 (2017), doi:10.1364/OE.25.023254 |

See also: mode locking, active mode locking, soliton mode locking, mode-locked lasers, femtosecond lasers, mode-locked fiber lasers, mode-locked diode lasers, ultrashort pulses, double pulses, saturable absorbers, mode locking devices, semiconductor saturable absorber mirrors, Kerr lens mode locking, self-starting mode locking, additive-pulse mode locking, Q-switching instabilities, Q-switched mode locking, pulses, pulse characterization, pulse propagation modeling, timing jitter, The Photonics Spotlight 2008-05-13

and other articles in the categories lasers, light pulses, methods

|

If you like this page, please share the link with your friends and colleagues, e.g. via social media:

These sharing buttons are implemented in a privacy-friendly way!