Fiber Amplifiers

This is part 4 of a tutorial on fiber amplifiers from Dr. Paschotta. The tutorial has the following parts:

1: Rare earth ions in fibers, 2: Gain and pump absorption, 3: Self-consistent solutions for the steady state, 4: Amplified spontaneous emission, 5: Forward and backward pumping, 6: Double-clad fibers for high-power operation, 7: Fiber amplifiers for nanosecond pulses, 8: Fiber amplifiers for ultrashort pulses, 9: Noise of fiber amplifiers, 10: Multi-stage fiber amplifiers

Part 4: Amplified Spontaneous Emission

In any laser amplifier, we need to have some laser-active ions in excited (metastable) states as a precondition for stimulated emission. Unavoidably, we then also get some spontaneous emission. The resulting fluorescence light goes into all directions and mostly leaves the fiber on the side. (With an infrared viewer, one can see the pumped fiber “glowing”.)

A tiny part of the fluorescence light is captured by the fiber core and propagates together with any pump and signal along the fiber (in both directions). Importantly, it can then experience a similar gain as any signal. As fiber amplifiers often reach a high gain (tens of decibels), the guided part of the light from spontaneous emission is strongly amplified. We call that amplified spontaneous emission (ASE). The resulting power can become much larger than the power radiated into all other directions, even though only a minor part of the fluorescence is captured by the core.

The consequences of amplified spontaneous emission are:

- We may obtain a substantial output power in any wavelength region where the amplifier gain is high, even if we do not inject any input signal. That ASE light is relatively broadband; it is actually used in some superluminescent sources.

- If ASE copropagates with a signal, it constitutes a broadband noise for that signal.

- Strong ASE can cause substantial gain saturation: via stimulated emission, it lowers the excitation density and thus the amplifier gain. It causes a kind of soft gain clamping: more pump power still increases the gain, but only slightly, as the ASE powers grow rapidly with increasing gain.

Note that the gain clamping by ASE is most unwelcome when we need to amplify signals at wavelengths far from the gain maximum. Essentially, ASE limits the peak gain, and our signal gain may be much weaker than that. There are even cases where a device cannot work at all because of ASE. For example, it is not easy to make efficient high-power ytterbium-doped fiber lasers emitting at 975 nm, because it can be hard to suppress ASE at longer wavelengths. A similar case for an amplifier is shown in part 6 of this tutorial.

What Determines the Strength of ASE?

A critical factor for ASE is the amount of amplifier gain. As a rule of thumb, ASE becomes substantial above roughly 30 dB. We can still achieve signal gains of the order of 40 dB in a single amplifier stage, but usually not much more than that.

However, the gain is not the only relevant parameter:

- The more guided modes a fiber has, the more fluorescence light can be captured, and the stronger will be ASE. The minimum possible amount of ASE is obtained for a single-mode fiber. Basically all low-power fiber amplifiers are based on single-mode fibers, whereas high-power devices often have a few-mode fiber, exhibiting stronger ASE.

- For laser-active ions with quasi-three-level behavior (see part 3), ASE is significantly enhanced (normally by a few decibels). This is because we need a higher excitation density for a given amount of gain in order to overcome the signal reabsorption, and that causes stronger spontaneous emission. That effect is particularly pronounced for ASE in a direction where the excitation density at the beginning of the fiber is low. Therefore, ASE is often stronger in a direction opposite to that of the pump.

Example 1: ASE in an Ytterbium-doped Fiber Amplifier Pumped at 940 nm

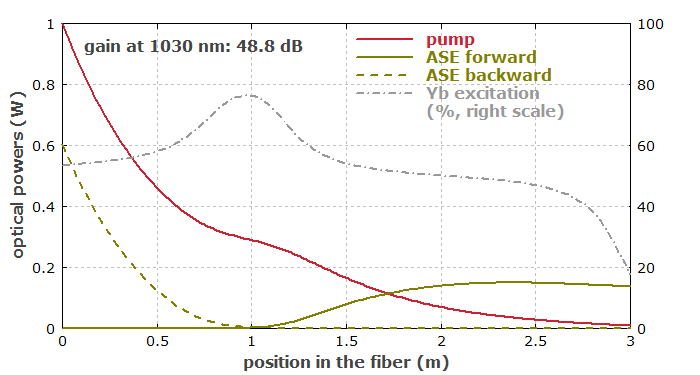

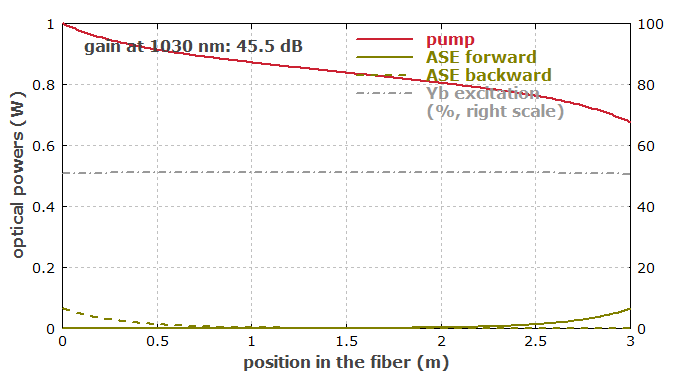

As an example, we consider an ytterbium-doped single-mode fiber pumped with 1000 mW at 940 nm. No signal is injected. Figure 1 shows that a substantial ASE power results in forward direction, and even more in backward direction. ASE has a pronounced impact on the Yb excitation density, which reaches it maximum not where the pump is strongest (at the left end), but rather approximately where ASE is weakest. Due to the resulting evolution of excitation density, the pump power decays in a somewhat irregular fashion: first quite fast, than more slowly, then faster again.

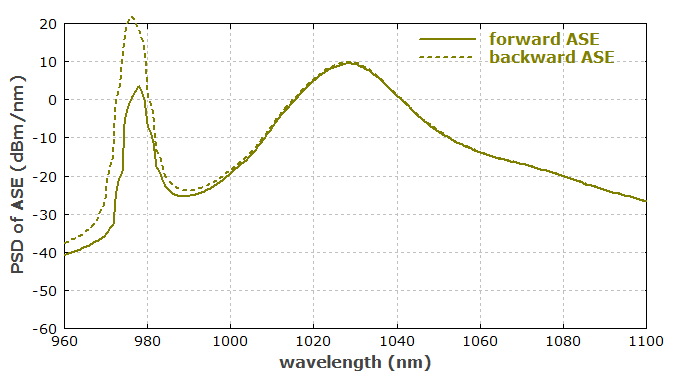

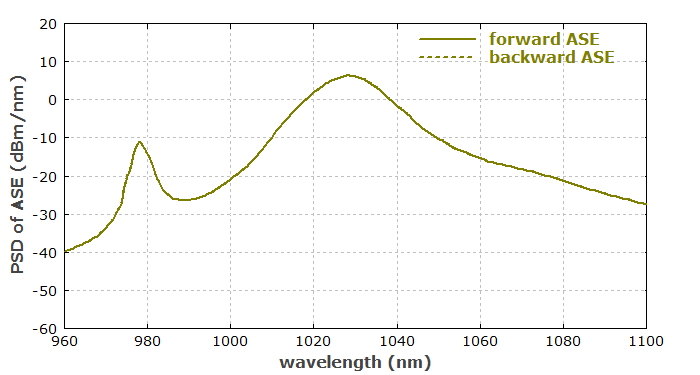

We now look at the ASE spectra at the fiber ends in forward and backward direction:

In the long-wavelength region (1060 nm and longer), there is hardly any difference between forward and backward ASE, because here the ytterbium ions show a nearly pure four-level behavior. Around 975 nm, however, backward ASE is stronger by orders of magnitude, and provides more power than the spectrally broader peak at longer wavelengths. We can understand this difference as follows:

- In the last third of the fiber length, the excitation density is below 50%, and there is net absorption at 975 nm. Forward ASE is strongly attenuated in that region, and only long-wavelength ASE makes it to the end.

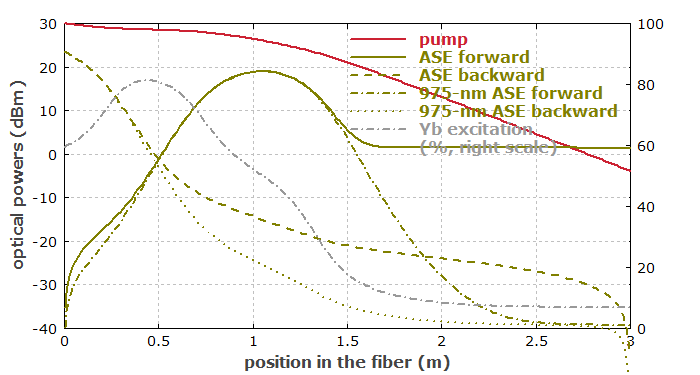

- That region with low excitation contributes a lot of spontaneous emission as a seed for backward ASE, even though the net gain is negative there. We see this clearly in Figure 3, where the powers are plotted with a logarithmic scale:

Backward ASE, starting at the right fiber end, continuously grows even in the region of negative net gain. (This is also true for the 975-nm part of the ASE, which has been plotted separately in addition.) Therefore, backward ASE can start at a much higher level once it gets into the region with positive net gain. On the other hand, forward ASE around 975 nm is strongly attenuated towards the end.

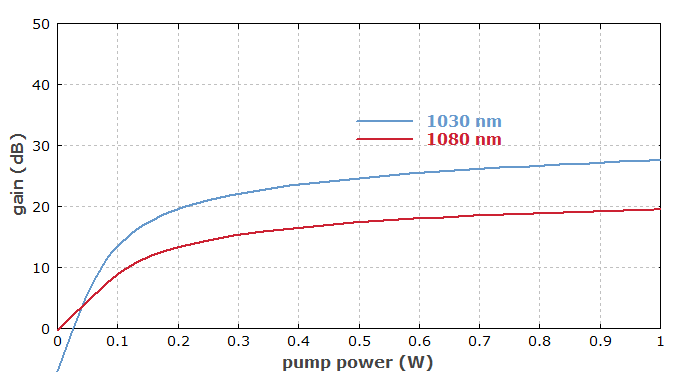

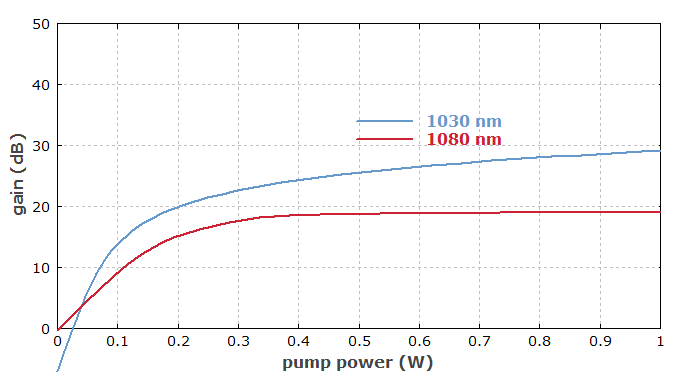

The fiber's gain at 1030 nm has been found to be 44 dB. Of course, ASE is the limiting factor. (In a theoretical situation without any ASE, one could have 76 dB in the configuration, and even more for a longer fiber.) Figure 4 shows how the small-signal gain at two wavelengths depends on the pump power. Already above 100 mW pump power, ASE starts to reduce it.

Example 2: ASE in an Ytterbium-doped Fiber Amplifier Pumped at 975 nm

The ASE behavior can strongly change if we change the pump wavelength. As an example, let us pump the same fiber as before, but at 975 nm instead of 940 nm. In that case, there can never be net gain at 975 nm, as stimulated emission by the pump limits the excitation density to roughly 50%.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of powers and Yb excitation:

It might be very surprising that pump power can now no longer be fully absorbed in the 3 m of fiber, although the absorption cross section at 975 nm is much higher than at 940 nm. This phenomenon is not due to ASE; it occurs also for lower power levels where ASE is weak. The reason is stronger pump saturation for 975 nm. The perhaps best way to understand it is to consider that the energy of absorbed pump light must be dissipated via spontaneous emission; the Yb ions have no other way to get rid of that energy, and can on average only absorb as many photons as they can radiate away. The lower excitation density achieved with 975-nm pumping (due to strong stimulated emission) implies that less energy is radiated per centimeter of fiber, and less pump power can be absorbed. A less important factor is that 975-nm photons have a lower energy, so you get more of them for the same power.

We now look at the ASE spectra in forward and backward direction, and see that these are now nearly identical:

The 975-nm peak is still there, but it is much weaker, as it does not see a positive net gain anywhere in the fiber.

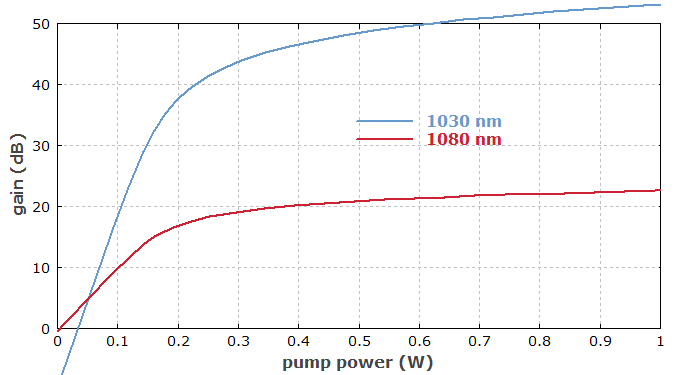

Figure 7 shows again the dependence of 1030-nm gain on pump power.

The shape of the curve has change a lot against the case with a 940-nm pump; there is a harder gain clamping. That, however, is related to the fact the pump power is not fully absorbed any more; above a certain level, any additional pump power only comes out at the other end. With a somewhat longer fiber, the results look different:

Interestingly, for 200 mW pump power the longer fiber delivers less gain at 1030 nm than the shorter fiber. For the 1080-nm gain, this is not the case. The stronger reabsorption at 1030 nm is behind that.

How to Minimize ASE

It has become clear now what measures could be taken to minimize ASE:

- The easiest is to limit the peak gain.

- We should use a single-mode fiber rather than a multimode fiber.

- A polarizing fiber, where light only with one linear polarization direction is guided, would be even better, if the signals to be amplified are polarized.

- If our laser transition has a quasi-three-level nature (as usual in fiber amplifiers), we should keep the excitation density at both ends as high as possible.

- In the next part, we will see that backward pumping may be better than forward pumping.

It can also be very helpful to use an amplifier chain consisting of two or more amplifier stages, and to filter out ASE in between the stages.

Go to Part 5: Forward and Backward Pumping or back to the start page.

Questions and Comments from Users

Here you can submit questions and comments. As far as they get accepted by the author, they will appear above this paragraph together with the author’s answer. The author will decide on acceptance based on certain criteria. Essentially, the issue must be of sufficiently broad interest.

Please do not enter personal data here; we would otherwise delete it soon. (See also our privacy declaration.) If you wish to receive personal feedback or consultancy from the author, please contact him e.g. via e-mail.

By submitting the information, you give your consent to the potential publication of your inputs on our website according to our rules. (If you later retract your consent, we will delete those inputs.) As your inputs are first reviewed by the author, they may be published with some delay.

These sharing buttons are implemented in a privacy-friendly way!